- Contents (Scroll down or Click on Section name to view)

- Preface

- Background

- DNA Proof

- Proof that William Lunsford, Esquire was the Son of a Knight

- Evidence

- Esquire as defined by Sir John Ferne

- Esquire as defined by William Camden

- Esquire as used in English Common Law according to Sir Edward Coke

- Esquire as defined by John Weever

- Esquire as used in Virginia

- Analysis

- Conclusion

- Evidence

- Proof that William’s birth was legitimate

- Evidence

- Analysis

- Conclusion

- Documentary Proof that William Lunsford, Esquire was the son of Sir Thomas Lunsford

- Evidence

- Analysis

- Conclusion

- Resolution of Objections to This Proof

- There is no Record of William Prior to 1650 - True but not conflicting

- William Lunsford, son of Sir Thomas, Died in Infancy - False

- William Was a Nephew, Cousin or Other Relative - False

- Failure to Inherit Estate - True but not conflicting

- William's Children had no Entitlement to Sir Thomas's lands - True but not conflicting

- William Not in Pedigree - True but not conflicting

- Allegedly Strange Titles in 1650 Document- False

- Richardson and ODNB -False claims

- Esquire Tells Us Nothing? - False

- Heraldic Societies Declared the Lunsford Line Extinct - True but not conflicting

- Instances of Esquire being used for people whose father was not a knight - True but not conflicting

- Ferne, Camden, Coke, & Weever were wrong - False claim

- William was not the Headright of Sir Thomas - False claim

- Other Confirming Evidence

- Arrival in Virginia

- Crozier & Coppage

- The Other Children Didn't Claim Estate

- Summary

- I have substituted a modern ‘s’ for the ancient long ‘s’, then written as ‘f’

- 17th-century printers indiscriminately replaced u with v and vice versa. I have replaced ‘u’s and ‘v’s as necessary to improve readability.

- Background

- Sr. Thomas Luntsford, Knight & baronett is obviously Sir Thomas Lunsford, knighted in 1641.

- The Lady Luntsford is presumed to be Lady Katherine (Neville) Lunsford, the 2nd wife of Sir Thomas although some sources claim she is Lady Elizabeth (Wormley) Lunsford, 3rd wife of Sir Thomas. Her identity is not germane to the answer to our question.

- Mrs. Elizabeth Luntsford is clearly Miss Elizabeth Lunsford, the daughter of Sir Thomas, with no evidence of dissenting opinions.

- Mrs. Philippa Luntsford is clearly Miss Phillippa Lunsford, the daughter of Sir Thomas, with no evidence of dissenting opinions.

- Mrs. Mary Luntsford is clearly Miss Mary Lunsford, the daughter of Sir Thomas, with no evidence of dissenting opinions.

- Wm Luntsford, Esqre is said, by some authors, [Crozier] & [Coppage] to be William Lunsford, Esquire, the son of Sir Thomas; yet, other authors[ODNB] & [Richardson] fail to list William as a son. These conflicting and unsourced claims are the impetus for our genealogical question: Was William Lunsford, Esquire the son of Sir Thomas Lunsford?

- Note: In the 17th-century, Mrs. was the abbreviation for Missus or Mistress[Bailey]. Ben Zimmer, executive editor of vocabulary.com and language columnist for The Wall Street Journal, when speaking of the etymology of the word mistress, said “...when it enters English, which happens in the 14th century - it comes in via French - it's basically just the feminine form of master.”[Zimmer] Master is an antiquated title for an under-age male. [WE] Thus, a 17th-century person would draw no inference about a woman’s age or marital status from the title Mrs. whereas a 21st-century person would assume the woman was married or a widow. All of which emphasizes the need to pay strict attention to the etymology of words when trying to glean information from old documents.

- An Original Source is a document, record, etc. that was recorded at, or about, the time of the event it describes.[BCG]

Primary Information is information from someone with first-hand knowledge (i.e. an eyewitness, a participant, an expert).[BCG]Evidence

- The autosomal DNA of seven of William's descendants matches a significant number of other descendants from the male Lunsford line[lunsfordDNA] making it better than 99% likely that William was a close relative of Sir Thomas.

- The autosomal DNA of William's descendants matches that of a significant number of descendants of the relatives and ancestors of Katherine Neville,[nevilleDNA] the second wife of Sir Thomas.

- The autosomal DNA of William's descendants matches that of descendants from the Smythe relatives and ancestors of Elizabeth Smythe, mother of Katherine Neville who was the wife of Sir Thomas Lunsford and the maternal grandmother of William Lunsford,Esquire.

- The autosomal DNA of William’s descendants matches that of descendants from the Fludd ancestors of Katherine Fludd, Sir Thomas’s mother and the paternal grandmother of William Lunsford, Esquire

- The autosomal DNA of William’s descendants matches that of descendants from the Apsley ancestors of Anne Apsley, Sir Thomas’s paternal grandmother and the great-grandmother of William Lunsford, Esquire.

Analysis

The Lunsford, Fludd, and Apsley DNA only proves that William belongs in the same Lunsford line as Sir Thomas. He may have been related as a son, cousin, distant cousin, nephew, or some other relative. However, since none of us have any other Neville ancestors (other than Katherine), our Neville DNA could only have been the product of a Lunsford/Neville marriage. The only one that has ever been found is Sir Thomas and Katherine Neville. Ah ha! you say: just because we can't find another Lunsford/Neville marriage doesn't mean one does not exist. If such a marriage did exist, it would have to be some other Lunsford with some other Neville. Well, I'm not done yet, The only possible way that we could have gotten so much Lunsford, Neville, Smythe, Fludd, and Apsley DNA is through William Lunsford, Esquire and his parents Sir Thomas Lunsford & Katherine Neville, his maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Smythe, his paternal grandparents, Thomas Lunsford & Katherine Fludd, and his great-grandparents, Sir John Lunsford & Anne Apsley. The odds are astronomically against seven of William's descendants coincidently getting all that Lunsford/Neville/Fludd/Apsley DNA by any other means.William's mother, Katherine Neville, married Sir Thomas in 1640 and she died in 1649. Thus William was no more than 8 or 9 years old when he was named as a headright for Sir Thomas in 1650.

Conclusions

1. William was the son of Sir Thomas; so, in the case of our dueling biographers whose works reflect the controversy about William’s father:- Crozier and Coppage have been vindicated by DNA.

- The ODNB version has been disproved by DNA.

- Richardson never weighed in on the subject but those who claim his silence is evidence that William was not the son of Sir Thomas no longer have a leg to stand on.

2. William was a minor in 1650.

- Proof that William Lunsford, Esquire was the Son of a Knight

- The eldest son of a knight or baron.

- attendants to the body of the king.

- appointments to high office by the king.

- Members of the upper echelons of the Virginia government such as members of the council of Virginia (many instances), Secretary of State (only 2 instances), Treasurer (only 1 instance), and Auditor General (only 1 instance).

- The eldest son of a knight or baron.

- Original (having been published about the time William was called an esquire),

- the information is Primary (the authors were recognized experts in the field of heraldry and English titles of nobility),

- and the evidence is Direct (it is explicitly stated).

- Evidence

- Esquire as defined by Sir John Ferne

Sir John Ferne was an English writer on heraldry. He matriculated from St John's College, Cambridge in 1572, was said to have studied at Oxford, and was admitted to the Inner Temple (became a barrister) in 1576. He served as a secretary in the Council of the North (1595–1609). He was elected Member of Parliament for Boroughbridge in 1604, sitting until 1609 (the year of his death). [Wikipedia] In 1586, Sir John Ferne in his book, Blazon of Gentrie, spoke of esquires by creation, birth, dignity and office, specifying the circumstances that conferred the title. [Ferne]

Note: Although the book was published 14 years before the start of the 17th century, we know Ferne’s definition would have still been in use in 1650 because it is corroborated by other definitions from independent sources that actually were written in the 17th-century.

Ferne defined esquires as:

- "Judges and Barons of the Benches, and Courts of Justice"

🛑 There's no evidence William was a Judge or Baron of any court or that he was ever a lawyer. - "Advocate, and procurators of the Soveraigne"

There was no king in 1650--England was a commonwealth, without a king, from 1649 to 1660.[Wikipedia] 🛑 There is no evidence William was an advocate or procurator prior to the execution of Charles I. - "Serjeaunts at the coyfe."(coif)

Serjeants at the Coif were the most elite of barristers who were the only ones allowed to practice in the higher courts of England. [Wikipedia] 🛑 Since William was a youmg child, he could not have been a serjeaunt at the coif. - "offices of Sheriffe, Eschetor or Serjeaunt at Armes"

🛑 Since William was a young child, he could not have held such an office. Furthermore, no evidence of this type of esquire can be found in Virginia. - "Eldest borne of a Baron and peere of the Realme or that of a Knight"

🛑 There were no Lunsford Barons or Peers of the realm; so, eldest born of a knight is the only one of Ferne’s definitions that could have applied to William Lunsford,

Esquire.

is the only one of Ferne’s definitions that could have applied to William Lunsford,

Esquire.

- "Judges and Barons of the Benches, and Courts of Justice"

- Esquire as defined by William Camden

William Camden (1551–1623) was Clarenceux King of Arms. [Wikipedia] Of all possible sources, he must be considered the most authoritative because as Clarenceux King of Arms, he was responsible for the Heraldic Visitations to gather pedigrees, to register coats of arms, and to halt and prevent abuse of heraldic titles and symbols. Camden defined five sorts of esquire in the following transcription of his original 17th-century work.

Transcription of Camden’s work at the University of Portsmouth (England) website:

“19. Next in degree after these Knights are Esquires, termed in Latine armigeri , that is Costrels or Bearers of armes, the same that scutiferi , that is, Shield-bearers and homines ad arma , that is, men at armes: the Gothes called them schilpor all, of carrying the shield, as in old times among the Romans such as were named scutarii , who tooke that name either of their Escutcheons of armes, which they bare as Ensignes of their descent, or because they were armour-bearers to Princes or to the better sort of the Nobilitie. For in times past every Knight had two of these waiting upon them: they carried his morion [helmet] and shield, as inseparable companions they stucke close unto him, because of the said Knight their Lord they held certaine lands in Escutage, like as the knight himselfe of the king by knights service. But now adaies there be five distinct sorts of these: for those whom I have spoken of alreadie be now more in any request. The principall Esquiers at this day those are accounted that are select Esquires for the Princes bodie, the next unto them be knights eldest sonnes and their eldest sonnes likewise successively In a third place are reputed younger sonnes of the eldest sonnes of Barons and of other Nobles in high estate, and when such heires males faile, togither with them the title also faileth. In the fourth ranke are reckoned those unto whom the King himselfe, togither with a title, giveth armes or createth Esquires by putting about their necke a silver collar of SS and (in former times) upon their heeles a paire of white spurres silvered, whereupon at this day in the West parts of the kingdome they bee called white-spurres for distinction from knights, who are wont to weare gilt spurres. And to the first begotten sonnes of these doth the title belong. In the fifth and last place be those ranged and taken for Esquires, whosoever have any superiour publicke office in the Commonweale, or serve the Prince in any Worshipfull calling. But this name of Esquire, which in antient time was a name of charge and office onely, crept first among other titles of dignitie and worship (so farre as ever I could observe) in the reigne of Richard the Second.”[Camden]

In regards to Camden’s definition "select Esquires for the Princes bodie", 🛑 there is no evidence William was ever a select Esquire for the prince's body and there was no king in 1650.

"knight’s eldest son"

is Camden’s only definition that could have applied to William Lunsford, Esquire.

is Camden’s only definition that could have applied to William Lunsford, Esquire.

Camden’s definition "younger sonnes of the eldest sonnes of Barons and of other Nobles in high estate" 🛑 could not apply to William because there were no contemporary Lunsford Barons or other Nobles in high estate.

Camden’s definition "those unto whom the King himselfe, togither with a title, giveth armes or createth Esquires by putting about their necke a silver collar of SS and (in former times) upon their heeles a paire of white spurres silvered" 🛑 would not apply to William Lunsford, Esquire because there is no evidence of any Lunsford ever being a “White Spur” knight. [Shaw] The title White Spur was very rare and only three families are known to have held it, one in modern times. [Wikipedia]

Camden’s definition "those ranged and taken for Esquires, whosoever have any superiour publicke office in the Commonweale, or serve the Prince in any Worshipfull calling" 🛑 could not apply to William Lunsford, Esquire because there is no evidence he ever held such an office and there was no king in 1650.[Wikipedia]

- Esquire as used in English Common Law according to Sir Edward Coke

Sir Edward Coke (1552 – 1634) was an English barrister, judge, and politician who is considered to be the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras. [Baker] He held the offices of Attorney General for England and Wales, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, and others. On page 667 of his Institutes of the Lawes of England, Coke wrote:

“The sonnes of all the peers and lords of parliament, in the life of their fathers, are in law esquires and so to be named. By this statute the eldest son of a knight is an esquire." [Coke]

Note:The statute referenced is Stat. de I H. 5. Cap. 5. Of Additions, a law requiring that a man’s name in any original writ must include the addition of his title of dignity or title of worship, under penalty of law if omitted. Coke expounds on the requirements for a title of dignity or title of worship.

“The sonnes of all the peers and lords of parliament 🛑 would not apply to William Lunsford, Esquire because there were no contemporary Lunsford peers or Lords.

"eldest son of a knight is an esquire."

under Coke's interpretation of English Common Law applies to William Lunsford, Esquire.

under Coke's interpretation of English Common Law applies to William Lunsford, Esquire. - Esquire as defined by John Weever

John Weever (1576–1632) was an English antiquarian and poet, best known--among other things-- for his Ancient Funerall Monuments, the first full-length book to be dedicated to the topic of English church monuments and epitaphs, which was published in 1631, the year before his death.[Wikipedia] Weever spoke of "the signification and Etymology of the name Esquire." He described what Esquires had been in the past and wound up by saying "But these Esquires, of whom I have already spoken be now no more in any request; five distinct sorts are onely remaining of these at this day:"[Weever]

- "Select Esquires for the Princes bodie",

🛑 There is no evidence William was ever a select Esquire for the Prince's body and there was no king in 1650. - "knights eldest sonnes"

This is Weever’s only definition that could have applied to William Lunsford, Esquire.

This is Weever’s only definition that could have applied to William Lunsford, Esquire. - "Younger sons of the eldest sons of barons and other Nobles in higher estate"

🛑 This definition could not apply to William Lunsford, Esquire because there were no contemporary Lunsford Barons or other Nobles in high estate. - "those unto whom the King himselfe, together with a title, giveth Armes, or createth Esquires by putting about their necke a silver collar of *SS, and (in former times) upon their heeles a paire of

white spurs, silvered"

🛑 This definition could not apply to William Lunsford, Esquire because there is no evidence of any Lunsford ever being a “White Spur” knight. [Shaw] The title White Spur was very rare and only three families are known to have held it, one in modern times.[Wikipedia] - "Whosoever have any superior publicke Office in the common weale, or serve the Prince in any worshipfull calling" 🛑 Since William was a young child he could not have held a superior public office or served the king in any worshipful calling. There was no King in 1650.

- "Select Esquires for the Princes bodie",

- Esquire as used in Virginia

The title Esquire in 17th-century Virginia was much more limited and restrictive than the title in England. [NGY] The only esquires that can be found in Virginia records [esquires] were either:

- Sons of knights and barons

This is the only use of esquire in Virginia that could have applied to William.

This is the only use of esquire in Virginia that could have applied to William. - Members of the upper echelons of the Virginia government. [NGY]🛑 Since William was a young child, he could not have been in the upper echelon of Virginia government.

🛑 No other examples of esquires can be found in Virginia records.

The above chart was compiled from an exhaustive search through 17th-century Virginia records. [esquires]

- Sons of knights and barons

- Analysis

- Conclusion

- Proof that William’s birth was legitimate

- Evidence In 1586, Sir John Ferne in his book, Blazon of Gentrie, said the following of Bastards in regard to titles:

- Analysis

- Conclusion

- Proof that William Lunsford, Esquire was the son of Sir Thomas Lunsford

- Evidence

William Lunsford, Esquire was the son of a knight (proof is in section III above).

In all of history, only three Lunsford men have ever been knighted.

- Sir Thomas Lunsford paid for William Lunsford, Esquire's transportation and William's name was grouped with the rest of Sir Thomas's family in the 1650 land grant.[Nugent]

- Analysis

- Conclusion

- Resolution of Objections to This Proof

- There is no Record of William Prior to 1650 - True but not conflicting

- William Lunsford, son of Sir Thomas, Died in Infancy - False

- William Was a Nephew, Cousin or Other Relative - False

- Failure to Inherit Estate - True but not conflicting

- If the existence and/or whereabouts of the son were unknown and could not be discovered. There is evidence that William, while still a minor and an orphan, was “left to fend for himself in Northumberland County, Virginia.”[Coppage] This may be one plausible explanation as to why William did not inherit his father’s estate. The orphan William may not have realized that he was the rightful heir. He was, after all, living far away from his only blood relatives who could have told him. Of course, this is only speculation and it’s rendered a moot point by item 3 below. It should be pointed out that one of Sir Thomas’s daughters claimed the estate for herself while three of his daughters failed to make any claim. Did they fail to do so because they believed that their brother, William, the rightful heir, was still alive somewhere in Virginia?

- If there was an older brother still living (rule of primogeniture). There’s no evidence that this might be the case.

- If the son died after the death of his father and before the settlement of his father’s estate. Unsourced family trees claim that William died in 1663. The estate was not settled until seven years later. If the year of death is correct, this, alone, would explain why there is no mention of William in the settlement of his father’s estate.

- If the son’s birth was illegitimate, the son would not be an heir even if the mother and father later married. This could not have been the case because it was proved in section IV above that William’s birth was legitimate.

- If the father's will named someone else as his heir. This could not have been the case because the estate of Sir Thomas was settled without a will.

- William's Children had no Entitlement to Sir Thomas's lands - True but not conflicting

- William Not in Pedigree - True but not conflicting

- There is no name given for the first wife of Sir Thomas

- There is no name given for the son born to the first wife of Sir Thomas

- The given name for the first father-in-law of Sir Thomas is blank

- No birth info is given for Sir Thomas but it is given for some (but not all) of his siblings and some (but not all) of his children.

- The pedigree shows Barbara Lewknor as the paternal grandmother of Sir Thomas but Faris[faris] confirmed by DNA evidence shows his paternal grandmother was Anne Apsley.

- The pedigree says the will of Sir Thomas was dated 4 Jan 1688 and proved 13 Jun 1691; this misinformation could not have come from Sir Thomas because he died without a will by 1653.

- Allegedly Strange Titles in 1650 Document - False

- Richardson fails to mention William - True but not conflicting

- ODNB - False claims

- The ODNB claims Sir Thomas was born about 1610 but, an original parish record tells us he was born 1604 (new calendar).

[findmypast]

- The ODNB claims Sir Thomas was born in Sussex, England while an original parish register tells us he was born in Bearsted, Kent, England.

[findmypast] Bearsted was his mother’s hometown

and the place where his parents married (just 11 months before his birth)[findmypast].

- The ODNB claims Sir Herbert Lunsford was the twin of Sir Thomas but the only evidence is hearsay from an anomynous source first published about 100 years after Sir Thomas was born.

The 1603/1604 parish register for the birth/baptism of Thomas makes no mention of Herbert.

[findmypast]

- The ODNB claims William Lunsford was a son born to Ann Hudson in 1638 but there is no evidence. There is no original evidence for the mother’s given name--it is blank on the 17th-century

Lunsford pedigree.[Nichols] Apparently, the only original evidence for this son is the pedigree chart with no mention of when/where the child was born, when or where the child died, or what, if any,

name was given to the child. It is only unfounded speculation that the child’s name was William or that he was born in 1638. The truth is that DNA has established Katherine Neville (not Ann Hudson) as William's mother.

[nevilleDNA]

- The ODNB states that Sir Thomas’s 1650 Virginia land grant was in Lancaster County but Lancaster County did not exist in 1650[Wikipedia]. The grant was in Northumberland County.

- The ONDB states that the tombstone of Sir Thomas was moved from Rich Neck Plantation to Bruton Parish. Actually, it is unknown if there ever was a tombstone for

Sir Thomas. Certainly, there never has been one at the Bruton churchyard. The stone referenced by Richardson and the ODNB was a cenotaph (not a tombstone) reportedly placed over the grave of

Thomas Ludwell, Esquire by his nephew. Ludwell’s stone slab gives no dates and merely states that near this place (Rich Neck) lie the bodies of Richard Kemp and Sir Thomas Lunsford, kt.

In 1727, Ludwell’s nephew moved his uncle’s remains and the cenotaph to the Bruton churchyard but there is no evidence or mention that tombstones or remains of Richard Kemp or Sir Thomas Lunsford

were ever moved. By 1891, the cenotaph had been leaned against the wall of the church to preserve it.[Meade]

- The ODNB tell us that Elizabeth (last name at birth uncertain), widow of Richard Kempe, was the third wife of Sir Thomas; however, there is no uncertainty that her maiden name was

Wormely. The controversy is not over the Wormely name at birth but rather over which Wormely was her father.

- The ODNB says that Sir Thomas died in Virginia before 1 December 1656. Although technically correct, the date inferred from Coldham, bef. 11 Jan 1653/1654, is more accurate

- Richardson claims Ann (Hudson) Lunsford was buried in East Hoathly, Sussex, England while the ODNB claims Ann (Hudson) Lunsford was buried at Down Hatherley in Gloucestershire while other sources say she was buried in East Hoathly, Sussex, England. Parish registers for both locations still exist but there's no mention of Ann (or Mary) Lunsford in either. Also,there are no tombstones, or cemetery records for Ann (or Mary) from either location.

- Esquire Tells Us Nothing - False

- Heraldic Societies Declared the Lunsford Line Extinct - True but not conflicting

- Instances of Esquire being used for people whose father was not a knight - True but not conflicting

- Ferne, Camden, Coke, and Weever Were Wrong - False claim

- William was not the Headright of Sir Thomas - False claim

- Arrival in Virginia

- Crozier & Coppage

- The Other Children Didn't Claim Estate

- Summary

- Evidence

- Proof by DNA

- Proof by 17th-century Documents

- Proof by Common Sense

- Analysis

- Conclusion

- a descendant of William Lunsford, Esquire, and

- you have taken a DNA test at ancestry.com, and

- you would like to participate in a DNA study with the goal of reinforcing the proof for William's ancestry and gathering evidence for his wife(s) and their children,

- Bailey - Kent P. Bailey and Ransom B. True, A Guide to Seventeenth-Century Virginia Court Handwriting, pp. 29 & 37;

- Virginia Genealogical Society, 2001

- BCW - BCW Project, British Civil Wars, Commonwealth and Protectorate - Sir Thomas Lnsford c.1611-56 Open BCW source in another window or tab

- Note:The source for this biography is the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article by Basil Morgan and it repeats the same errors found in the ODNB.

-

- Camden - William Camden, Britain, or, a Chorographicall Description of the most flourishing Kingdomes, England, Scotland, and

- Ireland - A vision of Britain Through Time

, From a transcription at the University of Portsmouth (England) - Camden - William Camden, Britain, or, a Chorographicall Description of the most flourishing Kingdomes, England, Scotland, and

- Open Camden source in another window or tab Pages are not numbered. From Section 7, scroll down to THE ORDERS AND DEGREES OF ENGLAND, then scroll down to paragraph 19 for Camden’s definition of Esquire.

- Coke - Sir Edward Coke, Milite, J.C., Second Part of The Institutes of the Lawes of England, p. 667,

- a series of legal treatises published, in stages, between 1628 and 1644. Open [Coke] source in another window or tab

- Coldham - Peter Wilson Coldham, The Complete Book of Emigrants 1607-1660, 1987; pp. 244 & 269; Genealogical Publishing Co. Inc.;

- Baltimore, MD, 21202

- Coppage - A. Maxim Coppage and John E. Manahan, The Coppage-Coppege Family 1542-1955, printed 1955

- Open page 31 in another window or tab

Open pages 110, & 111 in another window or tab - Crozier - William A. Crozier, editor, Virginia Heraldica Vol V, p. 40; New York: The Genealogical Association, 1908

- Open page 40 in another window or tab

-

- esquires - List of esquires found in the records of 17th-century Virginia

- faris - David Faris, Plantagenet Ancestry of Seventeenth-Century Colonists, page 177; Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc.; Baltimore, Md.

- Ferne - Sir John Ferne, The Blazon of Gentrie, 1586.

- Those who are esquires. pages 100 & 101

- If the Armes of the reputed father shall descend to his Bastard? pages 288-298

- findmypast - Find My Past, a genealogy website in England

- England Marriages 1538-1973 Thomas & Katherine

- Kent Family History Society, Parish Records, Bearsted baptisms 1563-1847 birth of Thomas

- Kent Family History Society, Parish Records, Bearsted baptisms 1563-1847 birth of Thomas

- Hill - Ronald A. Hill, Ph.D., CG, FASG

- Interpreting the Symbols and Abbreviations in Seventeenth Century English and American Documents

- LDS - FamilySearch.org, England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975

- Lunsford - Michael Terry Lunsford, Sir Thomas Lunsford Bio-Study, 2001

- lunsfordDNA - An analysis of the ancestryDNA.com match lists for four of William's descendants.

- The match lists were filtered to include only those DNA matches to descendants of Sir Thomas Lunsford. Statistical analysis of the study results indicates a better than 99% chance that William was closely related to Sir Thomas. The study was conducted in 2018 and has not been updated for three new participants and for the thousands of new matches added for the original participants.

- Meade - Bishop William Meade, Old Churches, Ministers, and Families of Virginia

- Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott Company. 1891, pgs 194-

- nevilleDNA - A statistical analysis of the ancestryDNA.com match lists for seven of William's descendants.

- The match lists were filtered to include only those DNA matches who had no Lunsford ancestors but had a MRCA Neville ancestor in common with one of the seven participants in the study. To date (Nov 2021) 22 such matches have been found which confirms that William's parents were Katherine Neville and Sir Thomas Lunsford with 97% to 100% confidence. The study is ongoing with only about one-half of the full database examined to date. Open Neville DNA matches in another window or tab

- NGY - WeRelate.org, Nobleman, Gentleman, Yeoman in colonial Virginia

- Nichols - John Bower Nichols and son; ; Collectanea topographica et genealogica, Vol. IV. pp. 139-156; London, 1837

- Nugent - Nell Marion Nugent, Cavaliers and Pioneers Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants 1623-1666, pp. xxiv & 200.

- Abstracted from the original Virginia Patent Book Number 2 now archived in the Virginia State Library in Richmond

- by Nell Marion Nugent of the Virginia Land Office, Richmond, Virginia, 1934.

- Reprinted by Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., Baltimore, Maryland

- ODNB - Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, entry for Sir Thomas Lunsford.

- Note: The ODNB has been criticized by the British press for it’s inaccuracies.[Wikipedia]

- For instance, Vanessa Thorpe of The Observer wrote this about the 2005 edition:

[Thorpe]

"At £7,500 for the set, you'd think they'd get their facts right"- The biography for Sir Thomas Lunsford is one of those that failed to get the facts right. Lunsford’s biography, written by Basil Morgan in the 2005 edition, is riddled with errors. A Google and Bing search for Basil Morgan’s academic and professional credentials returned nothing except that he was archivist and tour guide at Rockingham Castle in Northamptonshire, England. Basil Morgan and Douglas Richardson wrote nearly identical biographies with the same errors so it’s not certain if this was coincidence, one copied from the other or, they both worked from bad sources. In any event, it’s obvious that neither did a modicum of fact-checking and both should carry less weight when compared to less error-prone sources. Sir Thomas Lunsford's biography in the 1895-1900 edition was written by William Arthur Shaw (see Shaw) and it appears to be more complete and free from the errors and unfounded speculation found in the 2005 edition.

- For instance, Vanessa Thorpe of The Observer wrote this about the 2005 edition:

- Oxford - Oxford English Dictionary

- Pedigree - Notes on Lunsford pedigree

- Prince - John Prince, Worthies of Devon (1810 edition, p. 236) As quoted or paraphrased from Weever’s Antient Funeral Monuments

- (See Weever)

- Richardson - Douglas Richardson. Royal Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families 5 vols,

- ed. Kimball G. Everingham (Salt Lake City: the author, 2013), Vol. III, p. 676

ALTHOUGH RICHARDSON IS OFTEN CITED AS A SOURCE FOR WILLIAM LUNSFORD,ESQUIRE, HE DOES NOT MENTION WILLIAM ANYWHERE IN HIS BOOK - Shaw - William Arthur Shaw, Litt. D (1865-1943) and George Dames Burtchaell, M.A. M.R.I.A. (1853-1921), The Knights of England,

- Vol. II, A complete record from the earliest time to the present day of the knights of all the orders of chivalry in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and of knights bachelors

, Sir John, p. 149, Sir Thomas p. 211,Henry/Sir Herbert p. 220, and Index.

Printed and Published for Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood, Lord Chamberlain’s Office, St. James’s Palace; Sherratt and Hughes, London, 1906.

Note: This source shows Henry Lunsford, Governor of Monmouth, was knighted 6 Jul 1645 but this is an obvious misprint because Henry was killed two years earlier and knighthood has never been awarded posthumously. Also, it was Herbert (not Henry) Lunsford who was the Governor of Monmouth. Citing Walkley in a later biography written for the ODNB, Shaw corrected the error by stating it was Herbert Lunsford who was knighted 6 Jul 1645.

- Stanhope - M. Stanhope,The Colonization of 17th Century Virginia by an English Kinship Group

- Stoyle - Mark Stoyle, The Cannibal Cavalier: Sir Thomas Lunsford and the Fashioning of the Royalist Archetype University of Southampton;

- Thorpe - Vanessa Thorpe, The Observer (London, 6 March 2005).

- "At £7,500 for the set, you'd think they'd get their facts right".

- Walkley - Thomas Walkley,

- A catalogue of the dukes, marquesses, earles, viscounts, bishops, barons of the kingdomes of England, Scotland, and Ireland, with their names, sirnames, and titles of honour whereunto is added a perfect list of the lords; London; Reproduction of the original in the Magdalene College (University of Cambridge) Library

- WE - Master vs. Mister – What’s the Difference? Article at writingexplained.org.

- Webster - “Sqiure.” Merriam-Webster, Dictionary, Merriam-Webster.com

Accessed 14 Aug. 2021.

- Weever - John Weever (1576-1632), Ancient funerall monuments

- within the united Monarchie of Great Britaine, Ireland, and the Islands adiacent; published 1631. Pages 594-596 See also Prince

- Wikipedia - please see entries at:

- William Camden

- Commonwealth_of_England

- Dictionary_of_National_Biography

- Esquire

- Sir John Ferne

- Great Fire of London

- Lancaster County

- Prince

- Serjeant-at-law

- John Weever

- White_Spur

- Zimmer - Ben Zimmer,MistressHistory Of A Deeply Complex Word: The Many Meanings Of 'Mistress'

- transcript of a radio broadcast interview with Ben Zimmer on KJZZ National Public Radio on August 22, 2015.

- Walter Aston, Esquire - son of Sir Walter Aston

- Henry Berkeley, Esquire - son of Sir Maurice Berkeley

- Edmund Jennings, Esquire - son of Sir Edmund Jennings

- William Lunsford, Esquire - son of Sir Thomas Lunsford

- Capt. John West, Esquire - son of Thomas West, 2nd Baron De La Warr

- Henry Wyatt, Esquire - son of Sir Francis Wyatt

- Argoll Yeardly, Esquire - son of Sir George Yeardly

- William Barnard, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Capt. Richard Bennett, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Capt. Henry Browne, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Theodorick Bland, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- John Brewer, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Capt. William Brocas, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- The Honorable William Byrd, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Robert Carter, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Edward Diggs, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- William Ferrer, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Colonel Edward Hill, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Capt John Hobson, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Capt Francis Hooke, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Richard Kempe, Esquire - Secretary of State

- Col. Richard Lee, Esquire - Secretary of State

- Capt. John Lightfoot, Esquire - Auditor General of Virginia

- The Honorable Phillip Lightfoot, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- George Ludlowe, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Captain Samuel Macock, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Capt. Samuell Matthews, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- George Minifie, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Capt. William Pierce, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Edward Porteus, Esquire - Member of the Council of Virginia

- Robert Porteus, Esquire - Member of the Council of Virginia

- Capt. Thomas Purifoy (or Purifye), Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- John Rolfe, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Georg Sandys, Esquire - Treasurer of Virginia

- Capt. Adam Thorogood, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Captain George Thorpe, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Capt. John Utye, Esquire - Member Council of Virginia

- Colonel Abraham Wood, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- Capt. Ralph Wormeley, Esquire - Member of Council of Virginia

- (none)

Was William Lunsford, Esquire the son of Sir Thomas Lunsford?

List of Esquires in 17th-century Virginia

Was William Lunsford, Esquire the son of Sir Thomas Lunsford?

Preface

Several renowned biographers and historians have weighed in on the identity of William Lunsford, Esquire. Unfortunately, they don’t agree and not one of them presents any original, primary, or direct evidence to support their position. If you’re the sort of person who thinks genealogic proof is only valid when it’s confirmed by a renowned biographer, genealogist, or historian, don’t waste your time on this proof. I am none of those. I am a retired systems analyst, who made a career out of gathering facts, analyzing facts, and drawing logical conclusions based on the facts. Herein is evidence, from original 17th-century sources, presented for those who prefer to draw their own conclusions.

The key evidence presented here is not new. So why hasn’t this evidence been presented before? The fact is that the sources have been tucked away in seldom visited corners of libraries and archives. They are generally not indexed and they are by no means an easy read--all but the most determined scholar will probably give up after a few pages. It has only been recently that these sources have made their way to the internet where computer search engines can bring significant parts to the attention of casual genealogists. Thus, I somewhat stumbled upon the 17th-century definition of esquire that unlocked the mystery of William’s origin. Others have correctly guessed the significance of esquire but their evidence has been overwhelmed by arguments of questionable logic (discussed in section VI. below) and by modern definitions of esquire that would have been unknown in the 17th-century. It cannot be emphasized enough that we must set aside our modern understanding of esquire and turn to definitions from authoritative 17th-century sources to correctly understand what the word really meant when written in 1650. After all, the best genealogy is all about high-quality evidence from original sources. I have gathered evidence as recorded in the 17th-century and draw inferences solely from that evidence. Please consider this evidence without bias or prejudice. It is my sincere hope that this new reckoning of knowledge will encourage other researchers to find additional evidence to tell us more about William’s life--there’s still much to learn and knowing who his parents really were gives us a good start for further research.

Source citations are indicated by a superscript source name enclosed with square brackets i.e. [sourcename] Hovering the mouse cursor over any [sourcename] will display a pop-up box with a brief description of the source. Try it here[sourcename]

If there is an online copy of the source, the [sourcename] will be underlined and highlighted in light blue. Clicking on a highlighted [sourcename] will open the source in another window or tab. This allows you to examine a source without losing your place in this document. Of course, there is still a traditional list of sources at the end of this document.

In this proof, I have highlighted direct quotes from 17th-century books in Gold. The quotes are exactly as originally printed, with the following exceptions:

Virgil Owens - 1 Sep 2021

In a Virginia land grant dated 24 Oct. 1650, Sir Thomas Lunsford, Knight & baronett was granted 3,423 acres in Northumberland County for transporting 65 persons into the Colony of Virginia[Nugent]. The first six names of persons transported were: “Sr. Thomas Luntsford, Knight & baronett, The Lady Luntsford, Mrs. Elizabeth Luntsford, Mrs. Phillippa Luntsford, Mrs. Mary Luntsford, Wm Luntsford, Esqre.” There were no other Luntsford, Lunsford, or similar surnames among the other 59 persons transported.

The fact that the surname was spelled Luntsford and not Lunsford is of no particular significance because names were frequently misspelled in 17th-century documents[Bailey] & [Hill].

We know that the Lunsford spelling is correct because that’s how Sir Thomas, himself, signed a letter to Prince Rupert in 1644.[Lunsford] And that's how the family name is spelled in

a 17th-century pedigree filed at the College of Arms in London.[Nichols]

In the 1650 document:

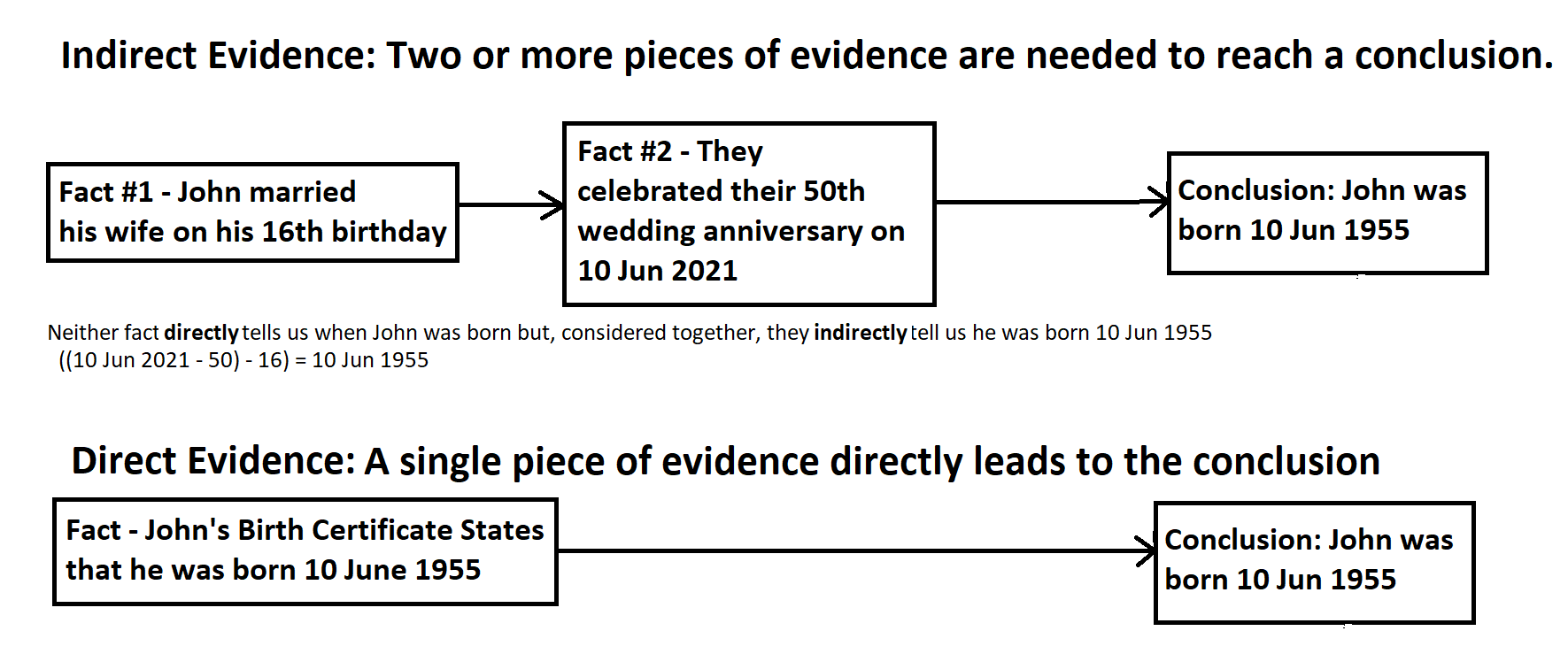

No direct evidence from an original source can be found that William was the son of Sir Thomas nor can any direct evidence from an original source be found that he was not. However, the indirect evidence from the 17th

century clearly indicates that William could only have been the son of Sir Thomas. The following illustrates

the difference between direct and indirect evidence:

Indirect evidence from original sources with primary information is just as valid as (in some cases better than) direct evidence. Consider that State and federal courts within the United States all allow the introduction of Indirect Evidence. In fact, many cases are tried and resolved without any direct evidence at all. After all, criminals usually avoid committing crimes where there might be witnesses or surveillance cameras and they are careful not to leave any direct evidence behind. Consequently, prosecutors are left with only indirect evidence to present to juries. Our jails are full of criminals serving very lengthy sentences because indirect evidence convinced jurors beyond a reasonable doubt of the defendant’s guilt.

By the same token, the combination of valid 17th-century indirect evidence presented in this paper should convince a logical and fair-minded person beyond a reasonable doubt that William Lunsford, Esquire was the son of Sir Thomas Lunsford. The indirect evidence that proves this is based on original 17th-century sources with primary information.

There is no evidence (direct or indirect) that would exclude William as the son of Sir Thomas; although, some attempts have been made to cloud the issue with "smoke screen", "red hering", and "straw man" arguments. I'll show in Section VI. below that such arguments are without merit because they are based upon hearsay, faulty logic, and false premises.

The indirect evidence for William's father has been hiding in plain sight all along. To see and understand it, we must abandon our 21st-century biases and notions and put ourselves into the mindset of a 17th-century person using 17th-century sources and definitions.

Authoritative sources from the 17th century tell us exactly what entitled a person to assume the title of Esquire. What's more, the same sources explicitly tell us that there were no other kinds of esquires at that time. And, this is borne out by an examination of early Virginia records, where every esquire mentioned was either a high-ranking member of the government of Virginia or the son of a Baron or Knight. Since William was never a high-ranking member of the Virginia government; and since, in all of history, there has never been a Lunsford Baron, William could only have been the son of a knight. But, which knight? That’s easy to prove because in all of history, there have only been three English knights with a Lunsford surname. [Shaw] & [Walkley]

The first was Sir John Lunsford [Shaw], who actually had a son named William Lunsford, Esquire but he can’t be William of the 1650 land grant because Sir John’s son died in 1580.The second Lunsford knight was Sir Thomas Lunsford. [Shaw]

The third Lunsford knight was Sir Herbert Lunsford [Shaw] & [Walkley], whose only son was named Thomas.[Lunsford] & [Nichols]

There is conflicting evidence if Henry Lunsford was ever knighted but it’s irrelevant because Henry died without issue.[Lunsford]

By process of elimination, Sir Thomas Lunsford is the only Lunsford knight who could have been William’s father.

Finally, I'll present DNA evidence that confirms and corroborates what the 17th-century sources tell us.

The word "esquire" has had an active etymology moving from strictly controlled and narrow definitions in ancient times to the modern definitions which are so broad that the title can apply to almost any modern male and many modern females. [Wikipedia] However, since our controversy stems from a 1650 Virginia document, intellectual honesty demands that we limit our search for the meaning of esquire to original 17th-century sources from the British empire while eschewing all other definitions to avoid an unconscious bias. To that end, an exhaustive search of Virginia records gives us a clear understanding of how esquire was used in actual practice in Virginia. But for explicit--by the book--definitions, we must turn to England, the mother country, because publishing did not exist in early Virginia. Only four original English sources with explicit definitions of esquire have been found.

All four are independent authoritative sources that corroborate one another’s definition(s). Each source gave several definitions which all boil down to just three conditions that would bestow the title of esquire to a 17th-century person in England:

The use of Esquire in 17th-century Virginia was even more restrictive than the English usage. For example, esquires who attended to or served the king did not exist in Virginia. Likewise, certain other positions of honor such as Sergeants at the Coif simply did not exist in Virginia. While the office of sheriff and some Justices of the Peace bestowed the title of esquire on the office holder in England, sheriffs and J.P.s in Virginia were not esquires. Examination of 17th-century Virginia documents (property record books, court orders, probate records, etc.) reveal only two circumstances where esquire was appended to a man’s name in Virginia: [NGY]

Not one instance of any other use of the title Esquire can be found in Virginia records.

Below, I will discuss the relevance (or lack thereof) to William for each definition offered by the English sources.

- Under the Board for Certification for Genealogists guidelines,[BCG] all the sources are

Please keep in mind that many of the offices, appointments, and positions that carried the title of esquire could not have been held by William Lunsford, Esquire, who was less than ten years of age (proved in section II. above)

I have kept the original spelling; so, please note that there were no spell checkers or

spelling dictionaries in the 17th-century. Most words were spelled as they sounded e.g. “now adaies” can be translated as “nowadays”, "coyfe"=coif" "fonnes"="sons",

"noe"="no", "alsoe"="also", etc. Other mispellings are more obvious. Archaic terms such as Prince or Prince's refer to the King of England.[Wikipedia]

After a reasonably exhaustive search, only four original 17th-century sources could be found for a definition of the title Esquire in England. All four sources are first-hand accounts recorded only a few years before the 1650 document by prominent and well-educated men. There can be no more authoritative source than William Camden, King Clarenceux of Arms--a position responsible for sending out Heralds on their Visitations to gather pedigrees, register coats of arms, and to halt and prevent abuse of heraldic titles and symbols. So, we know we are dealing with the most authoritative definitions appropriate for the time. There are multiple examples of esquires in the records of Virginia. All sources agree that “eldest son of a knight” is one situation that entitles a person to be styled as Esquire in both England and Virginia. And, we can see from the evidence in III.A.1 through III.A.5 that there is no other 17th-century definition or use of Esquire that could have applied to William Lunsford, Esquire.

Some vain attempts have been made to use 21st-century definitions of esquire and even squire to nullify the inescapable conclusion that William was the son of a knight. Of course, no one alive in 1650 could have had knowledge of the 21st-century definition. Their use of esquire could only have been in accordance with the everyday use as evidenced by 17th-century records and by contemporary treatises on heraldry and English common law as presented above.

WILLIAM LUNSFORD, ESQUIRE WAS THE SON OF A KNIGHT.

In the 17th-century (and well into the 20th-century in England), bastards were treated harshly under the law, having no standing in the courts with regards to inheritance of property or titles that may have come to them had their birth been legitimate. Once born a bastard, always a bastard in the eyes of English Common Law, even if the parents later married.

“Bastards are not of the parentage, or stock of the Gentle, and they being of the filthy and unclean and not worthy to be once named amongst the most excellent: for their mother being the concubine to their reputed father, cannot after his death participate or enjoy any part of the titles, or dignities of his father, as his lawful wife might do, and therefore the children proceeding from them both, be barred, as well from the rights and preeminence of sons as their mother is excluded from the rights due to relicts or widdows” [Ferne]

Ferne also said on page 278:“It is against nature if any good thing do proceede from a bastard. Upon which reasons, and also, to the rebuke of adultrie and unclean procreations, all laws, as well Ecclesiaticall and Martiall, as Civill, have denied any capacitie of succession to Bastards: for the law of Armes doth simply allow coate-armors no more to the bastard, or natural sonne of a gentleman then it doth to the son of a meanroturier, carter, peysant, burgess, or other ungentle estate within this Realme." [Ferne]

From the above evidence, it's clear that William Lunsford, Esquire was not a bastard because, in the 17th-century, all laws denied any capacity of succession to bastards and they were considered “unclean and not worthy to be once

named among the most excellent” and therefore could not hold a title of nobility such as Esquire.

WILLIAM LUNSFORD, ESQUIRE’S BIRTH WAS LEGITIMATE.

Since the evidence shows that William Lunsford, Esquire was the son of a knight, we know his father would have been a knight with a surname of Lunsford.

Only three Lunsford men have ever been knighted: Sir John, Sir Thomas, and Sir Herbert. Therefore William must have been the son of one of the three Lunsford knights.

Sir John actually had a son named William Lunsford, Esquire but that son died in infancy in 1580[Lunsford] so he could not possibly have been the headright in the 1650 land grant.

Sir Herbert had only one son but that son’s name was Thomas (not William).[Nichols]

Therefore, Sir Thomas Lunsford is the only Lunsford knight who could possibly be William's father. Furthermore, it was Sir Thomas who paid for William's transportation into Virginia and William's name was grouped

with the rest of the family on the 1650 land grant.[Nugent] Finally, William's descendants have inherited segments of Lunsford DNA[lunsfordDNA] and Neville DNA,[nevilleDNA]

which they only could have gotten from Sir Thomas and his second wife, Katherine Neville.

WILLIAM LUNSFORD, ESQUIRE WAS THE SON OF SIR THOMAS LUNSFORD

When this proof was first published online, a flurry of objections were raised by three individuals.Their objections are discussed below and, as you will see, most are based on false premises and unfounded speculation. Nobody has presented any 17th-century evidence that might disprove William as son of Sir Thomas. Which, leads one to ask why this controversy arose in the first place. Why has it been suggested that William was not a child of Sir Thomas, as were the other Lunsford children whose names were listed following Sir Thomas and Lady Lunsford in the 1650 land grant? The reason is simple: Biased and long-held opinions have been formed from the many false narratives and unfounded speculations about William--some of which have been circulating for centuries. It's only human nature that we turn a blind eye towards evidence that conflicts with our long held opinions and that we grasp at straws to find reasons to cling to our beliefs. For instance:

Not one original record can be found for William prior to 1650, leading one to question who his parents may have been. This could be a compelling piece of negative evidence were it not for the implications of esquire (noted in sections III through V above), the DNA evidence (in section VI below) and the loss of many records in the Great Fire of London.

DNA proves William's mother could only have been Katherin Neville,[nevilleDNA] who married Sir Thomas in 1640[findmypast]. During the 1640's, Sir Thomas appears to have resided in London except when he was off fighting for King Charles. Thus, any records for William would have probably been kept in London.

Unfortunately, just 16 years after the Lunsford family left for America, the Great Fire of London raged for four days, destroying 87 parish churches, most of the buildings of the city authorities, and the homes of 7/8ths of the population.[wikipedia] Any record of William would have, most likely, been destroyed in the fire.

Resolution: We should draw no conclusion about the absence of English records for William because of the high probability that they would have been destroyed in the Great Fire of London.

A 17th-century pedigree chart shows that Sir Thomas and his first wife (who was not named) had “a son and only child ob. infant ”[Nichols] Note: “ob.” is the

abbreviation for the Latin verb he/she died. Other than his existence, nothing else is known about this son from original source documents or from persons with first-hand information.

* His name is not known

* His birthdate is not known

* His birthplace is not known

* His date of death is not known

* His place of death is not known

* His place of burial is not known

Don’t believe me? Take a look at the sources for the above information at Wikitree and other genealogy sites None of the purported sources are original 17th-century sources and none of them cite an original 17th-century source. In fact, the missing details about this son have been filled in by biographers writing long after the fact who could not possibly have had first-hand information--in other words they were just guessing. Just because someone wrote something in a big book hundreds of years after the event does not make it true. Unless, of course, they back up their claim with an original source reference, which no one has done in the case of Sir Thomas and his son born to his unnamed first wife.

It was pure speculation that this son’s name might have been William. Other authors copied the name William without verification. It has been copied and repeated so many times that many people accept it as fact even though there is no valid evidence whatsoever.

In the same manner, it was pure speculation that the son was born and died about the same year as his mother’s death, e.g. 1638. There’s a bit of a problem with the 1638 date because between 1633 and 1639, Sir Thomas was either in prison or in exile in France, much of that time fighting for the King of France. Did his wife join him in exile and then return to England for the birth of the child? There’s no evidence that she did. There are huge problems with the died in infancy in 1638 theory: How could an infant who died in 1638 have been claimed as a Virginia headright 12 years after his death? Also, DNA evidence confirms that descendants of William of Virginia have both Lunsford and Neville DNA in their blood, which they only could have gotten via William's parents, Sir Thomas Lunsford, and his 2nd wife, Lady Katherine Neville (married in 1640[findmypast]). So, how could a dead infant leave traces of his DNA to posterity?

Some have tried to argue that William Lunsford, Esquire cannot possibly be the son of Sir Thomas because the son of Sir Thomas died in infancy. Any one who studied debate in high school will recognize this as a “Straw Man'' tactic; i.e. state a false premise and then use it to invalidate your opponent's position. The false premise here is that the son born to the first wife of Sir Thomas was named William while, in actual fact, nobody knows or can prove the name of that son.

Resolution: The argument fails to exclude William Lunsford, Esquire as a son of Sir Thomas Lunsford because the name of the son that died is unknown.

Preliminary DNA evidence coupled with the failure of the “William died in infancy theory” gave rise to a new theory that William Lunsford, Esquire must be a nephew, cousin or some other close relative of Sir Thomas. The problem with this theory is that no one has been able to find a William Lunsford, Esquire who actually was a nephew, cousin, or other relative and who was alive in 1650. Sir Thomas had a granduncle, William Lunsford, Esquire, who was the son of Sir John Lunsford but that granduncle died in 1580. Sir Thomas could not have had a nephew named William Lunsford, Esquire because:

* His brother, Herbert, had only one son, Thomas.[Nichols]

* His brother, Henry, died in 1643 and left no issue. [Lunsford]

* His brother, William, died (at age 19) in 1628 and left no issue.[Lunsford] & [Stanhope]

* His brother, John is presumed to have died in infancy and thus left no issue.

* His sisters did not marry men with a Lunsford surname[Lunsford] and thus would not have a son with a Lunsford surname.

Note: John Lunsford was baptized 30 Jul 1610 in Bearsted, Kent, England. [LDS] No record can be found for him after that date.

A reasonably exhaustive search failed to turn up any William Lunsford, Esquire who was living in 1650 and who was a cousin, nephew, or other close relative of Sir Thomas Lunsford.

More recent DNA evidence shows that William's mother was Katherine Neville, 2nd wife of Sir Thomas Lunsford. Therefore, William was a son, not a Nephew, Cousin or other close relative.

Resolution: The theory is unfounded because he was a son according to DNA evidence and a total lack of evidence from original sources to the contrary.

It has been argued that: since William Lunsford, Esquire did not inherit the estate of Sir Thomas, he was not his son. The fallacy in this argument is the assumption that a son would always inherit his father’s estate. There are, in fact, several reasons, under 17th-century English Common Law, why a son would not inherit his father’s estate:

Resolution: William did not inherit his father’s estate because he died before the estate was settled.

Michael Cayley noted that, in 1670, neither William nor his children were mentioned as having any interest in the lands of Sir Thomas. The statement is true enough but it's a "red hering" meant to mislead. First of all, William, himself, was already dead by 1670 so it's quite natural that he was not mentioned. As for William's children, English inheritance laws are (and were) based upon the principle that the heirs of a person who died intestate (such as Sir Thomas) would be that person's closest blood relative(s) still living. There was only one degree of separation between Sir Thomas and his four daughters who actually were mentioned in 1670. There was two degrees of separation between William's children and Sir Thomas; thus they were not his closest blood relative still living and thus there was no mention of them in 1670.

Resolution: The argument is a "red hering" that does nothing to prove or disprove William's parentage.

It has been argued that since there was no son named William in a 1647 pedigree drawn up by Sir Thomas Lunsford then that proves William was not the son of Sir Thomas.

First of all, we have to clear up the myth that Sir Thomas drew up a pedigree in 1647. There are several Lunsford pedigrees but only two original copies of a Lunsford pedigree that includes Sir Thomas are known to exist (one copy is in the College of Arms & the other is in the British Museum).[Nichols] Both copies are the same except for some notes and additions with dates after Sir Thomas died. The original pedigree with its accompanying proofs was entered with approval of the Kings of Arms at the College of Arms by memorandum of George Owen, York Herald, dated 1 Dec 1648. Owen attested that the chart agreed with the deeds and evidence presented. The same memorandum bearing the same date is in the file for the 1636 Visitation of Sussex. Sir Thomas could not have been present at the 1636 Visitation of Sussex because he was in exile in France fom 1633 to 1639.

It should be noted that there are several errors and omissions that are strongly indicative that the pedigree was NOT drawn up by Sir Thomas himself. [Pedigree]

It should also be noted that various unverified and inaccurate additions to the pedigree were made after 1 Dec 1648 (most of them after the death of Sir Thomas). For instance:

Finally, Sir Thomas was in prison from 1646 through 1648--first at the Tower of London and later moved to Lord Petre's house, a common prison for the Royalists.

Considering his inprisonment and the omissions and inaccuracies, it’s quite clear that the pedigree could not have been drawn up in 1647 by Sir Thomas, himself, nor at any time by anyone who was very knowledgeable about his family.

Be that as it may, we don't know if William was born before or after the date the pedigree was verified (1 Dec 1648). But even if he was born before the pedigree was drawn up, it is faulty logic to draw conclusions about a missing descendant because, by definition, a pedigree depicts ancestors but not necessarily all descendants along the main subject line. Descendants ouside of the main subject line in a pedigree chart are not part of the main subject line’s pedigree and thus are often not shown.

Resolution: Missing descendants of the main subject in a pedigree chart are the norm and prove nothing about the existence or non-existence of descendants. Also, it's unknown if William was born before or after the pedigree was drawn up

Michael Cayley has found it strange that in the 1650 grant, the three daughters had the title of “Mrs.” and, by implication, strange that William’s title was Esquire. Actually, it would not appear strange at all to a 17th-century reader because, in the 17th-century, Mrs. was the abbreviation for Mistress[Bailey] which at that time was the title for an unmarried female under the age of eighteen. As proved in section III above, according to 17th-century definitions, there is nothing strange at all about William’s title of Esquire. This all goes to emphasize that we must cast aside our biased 21st-century notions if we are to correctly understand what 17th-century documents actually tell us.

Resolution: There is nothing strange at all about the titles; thus, the argument fails because it is based upon a false premise.

Some have argued that William was not a son of Sir Thomas because Douglas Richardson did not name William as a son but I can find no evidence that Richardson has ever weighed in on the subject of William's parentage. In fact, William is nowhere to be found in Magna Carta Ancestry, Royal Ancestry, or any other work by Douglas Richardson!

Obviously, it would be impossible for Richardson, or any author, to list all the children and all the children’s children ad infinitum of every person in a multi-century genealogy. A line needs to be drawn somewhere. There will always be some missing generations of children and no inference should be drawn from that fact.

The Magna Carta Project at Wikitree.com describes the historian and author, Douglas Richardson as a reliable source. This has apparently caused two or three Magna Carta project leaders at wikitree.com to mistakenly believe that Richardson’s silence on the subject of William is evidence enough to disconnect William from Sir Thomas.

Apparently they did not read the introductions to Magna Carta Ancestry and Royal Ancestry, where Richardson, cautions that: “heavy reliance has been placed on heraldic visitations for the lists of children. Such sources are incomplete and, on occasion, inaccurate… …Every effort has been made to eliminate errors. All the same, no work of this sort dealing with so many families over so many centuries can be considered as representing a final determination of family relationships.” (my emphasis added) Richardson cited the Lunsford pedigree from the 1630’s heraldic visitations to Sussex as a source for his Lunsford information. That pedigree is rife with omissions, errors, and some reportedly fraudulent documents. [Pedigree]

Resolution: Total silence on a proposition is neither proof nor disproof of the proposition.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography claims William was not the son of Sir Thomas but does not cite an original or primary source.

The ODNB's claim about William's parentage conflicts with that of other authors, conflicts with the proof presented in this document, and conflicts with the DNA evidence from William's descendants. The ODNB has been criticized in the British press for its inaccuracies.[Wikipedia] For example, Vanessa Thorpe in the 6 March 2005 edition of The Observer (London) wrote the following about the ODNB :

I have listed below some specific errors found in the ODNB. I offer the following to point out that, in the very limited and narrow

context of the Lunsford family, other authors such as Crozier and Coppage have proven to be more credible.

Resolution: Because of the many inaccuracies, we cannot--in good faith--give much weight to the ODNB with regards to the family of Sir Thomas Lunsford. On the Lunsford-515 profile at Wikitree.com, Michael Cayley claims that esquire “was used for a rank of society below knights” and therefore does not necessarily prove William was the son of a knight.

Mr. Cayley seems confused about the English Hierarchy of Rank of Nobility system. Actually, a Baronet falls directly below a Knight in rank. Falling between the rank of Baronet and Gentleman is a consequence of being an esquire. It is not a definition

of what qualified a person to become an esquire. The qualifications for becoming an esquire in the 17th-century are outlined in section III above.

The fact that an esquire ranks lower than a knight and baronet does not deprive William of his title, Esquire, or its implication.

Besides being illogical, the argument is somewhat duplicitous in that “a rank of society below knights” is NOT a 17th-century definition of esquire at all; it is a modern definition of

squire[Webster] (wrong word and wrong time frame). Although Squire and Esquire both came from the same Latin root, each had already acquired distinctly

different meanings by the end of the middle ages:

In the English nobility system, rank and title are two different things. Title confers rank but it's never the other way around--one does not become an Esquire simply by ranking below a knight. In the 17th-century,

baronets, gentlemen, and yeomen also ranked below a knight but that, in no way, entitled them to use Esquire with their name. Contrary to Mr. Cayley’s assertion in Lunsford-515, William’s title tells us a great deal. It was proved in sections III and IV above that:

Resolution: The 17th-century definition of Esquire tells us a great deal about William's parents and his age. The assertion that "a rank of society below knights" tells us nothing about William

is a "Straw Man" argument because William was an Esquire, not a Squire. Lunsford researcher, Terry Lunsford, made the following statements:

“While heraldic societies declare the Lunsford crest "extinct," because Sir Thomas had no male heirs, it is certainly possible that we can still petition a claim to the arms if we can

trace back beyond Thomas, through another line”.[Lunsford] “Sir Thomas is commonly recognized as the "father" of all Lunsfords in the US. Nonetheless, tracing back to him is a task that has yet to be accomplished without extreme speculation

and assumption on the part of those who claim they have.”[Lunsford] The evidence in this paper disproves the claim that “Sir Thomas had no male heirs” and such evidence coupled with DNA evidence holds promise that--in the future--heraldic societies will

reverse their decision. In the meantime, rejection by a heraldic society is not--of itself--evidence that a line is extinct; it merely means that the heraldic society is not in

possession of sufficient evidence to prove descendants are entitled to display heraldic symbols.

Undiscovered proof for heraldic descent is not the same as proof of non-existence. Think of it this way: If I cannot find my birth certificate, it does not mean I’m not my father’s son;

but, until I find it, I probably cannot join the Sons of the American Revolution even though my 3rd great-grandfather was a documented continental soldier. It’s the same with William:

just because we can’t find his pedigree or baptismal record does not mean he’s not his father’s son; but, in the eyes of any heraldic society, the Lunsford line will remain extinct

until they are presented with proof that meets their requirements. Resolution: The declaration of an extinct line for heraldic purposes is not evidence that the line is biologically extinct. Mr. Cayley has expressed the opinion that in the 16th- and 17th-century visitations, and other records there were many esquires that were not sons of knights and therefore, William Lunsford, Esquire was not necessarily the

son of a knight. This argument is not logical. It is akin to saying many animals can’t fly... birds are animals therefore birds can’t fly. Neither example is logical. As pointed out in section III above, son of a knight was only one of several conditions that conferred the title esquire. Some esquires were the sons of knights and some were not.

It matters not how other people came

by the title of esquire, there was one and only one way William could have come by the title--and that was as the Son of a Knight.

Resolution: The argument is not logical Michael Cayley holds the opinion that the definitions of Ferne, Camden, Coke, and Weever were wishful thinking that did not represent what was happening in actual practise and did not include every type of esquire;

thus, according to him, esquire fails to prove William was the son of Sir Thomas. Mr. Cayley claims there are many examples of esquires in the Visitations by Heralds

that don't fit the definitions by the above 17th-century experts. However, when asked for specific examples, he refused to provide any and said he no longer wished to communicate with me on this subject.

In the 17th-century, Esquire was narrowly defined and strictly controlled by no less

authority than William Camden, King Clarenceux of Arms, the very man responsible for sending out heralds on their visitations.

Camden and Weever both mention other sorts of esquire but both made it clear that the other sorts were no longer in use and that that the five sorts they described were the only remaning Esquires. In the centuries following the 17th-century,

esquire gained all sorts of new meanings but, of course, people living in 1650 would not have had knowledge of future meanings. A thorough examination of 17th-century Virginia property records, court orders, and probate records

has not turned up a single example of an esquire who didn't fit the definitions of Ferne, Camden, Coke, and Weever. Certainly, these records are evidence of how esquire was used in actual practise in 1650 when it was appended to the name of William Lunsford.

Resolution: The argument has no merit because our 17th-century sources tell us there were no other sorts of esquire at that time and the person making the argument has failed to provide any evidence to support his case. In a WikiTree comment, Liz Shifflett claimed that Virginia headrights were sometimes bought, sold, and traded; thus, implying that William might not have been transported by Sir Thomas after all. What Mrs. Shifflett failed to mention was that when headrights

were sold or otherwise exchanged, the names of both the original owner and the final owner of the headright were always listed on the patent. This was because an original proof of payment for the transportation was

required by law. If the headright for William had been purchased, the seller's name would have appeared on the document. Since no former owner of William's headright was listed on the 1650 document, there is no doubt that

it was Sir Thomas who paid for William's transportation. Nell Marion Nugent is the most recognized expert on Virginia land patents. In her introductory explanation of headrights, she specifically refers to the

1650 grant to Sir Thomas Lunsford as an example of a person receivng land for having transported himself and others into Virginia.[Nugent]

Resolution: The claim is an unfounded smokescreen based upon a false premise

* Squire was an informal form of address used when speaking to (or referring to) a low-ranking landowner.

* Esquire, in the 17th-century, was a formal title of nobility. It was conferred on certain attendants to the king, certain office holders appointed by the king, and the eldest sons of Barons and Knights

(please see section III above for original 17th-century sources defining those permitted to use the title of esquire).

* Of all the documented 17th-century definitions for esquire, the only one that could have applied to William was the son of a knight.

* In all of history, there have only been three Lunsford knights in England

* Sir Thomas is the only one of the three Lunsford knights who could have been William’s father.

* William’s birth was legitimate, therefore

* his mother could only have been a wife of Sir Thomas and therefore

* William could only have been a minor in 1650.

* Of all the documented 17th-century definitions for esquire, the only ones that would apply to minors were Son of a Baron and Son of a Knight.

There were no contemporary Lunsford Barons; so, once again we are left with Son of a Knight as the only possible definition of esquire that could apply to William Lunsford, Esquire.

In 1649, Sir Thomas was given a pass to remove himself with his wife and children to Virginia [Coldham]. The 1650 land grant shows that Sir Thomas paid for the transportation of himself, his wife, and his children into the Colony of Virginia[Nugent]. William Lunsford’s name was listed next to the daughters of Sir Thomas, leading us to the logical conclusion that William was also a child of Sir Thomas.

Crozier, and Coppage both claim that William Lunsford, Esquire was probably the son of Thomas Lunsford.[Crozier] & [Coppage] And they have been proved right by DNA and original sources gleaned from the internet. DNA and the internet did not exist when Crozier and Coppage wrote about William. Critics have made much ado about Crozier and Coppage's use of the word "probably" as if it somehow takes away from their credibility and adds to the credibility of Richardson and the ODNB. With regards to Richardson, it's rather a "straw man" argument because nothing can be found about William in any of Richardson's books. The Oxford English Dictionary[oxford] defines the adverb “probably” as “almost certainly; as far as one knows or can tell." So, rather than detracting from Crozier & Coppage's credibility, it's a testament to their honesty about information derrived from the low quality and low quantity of evidence available to them at the time. In Crozier’s book, he correctly indicated in two places that Sir Thomas was married three times but he incorrectly states that Katherine Neville was the first wife of Sir Thomas. Although this was probably just a typo that got past the proof reader, it has been used as an attack on Crozier’s credibility. When compared against the many errors found in biographies at the ODNB (please see section VI. F. above), Crozier’s credibility certainly carries more weight than that of the ODNB.